by Tasmiah Akter

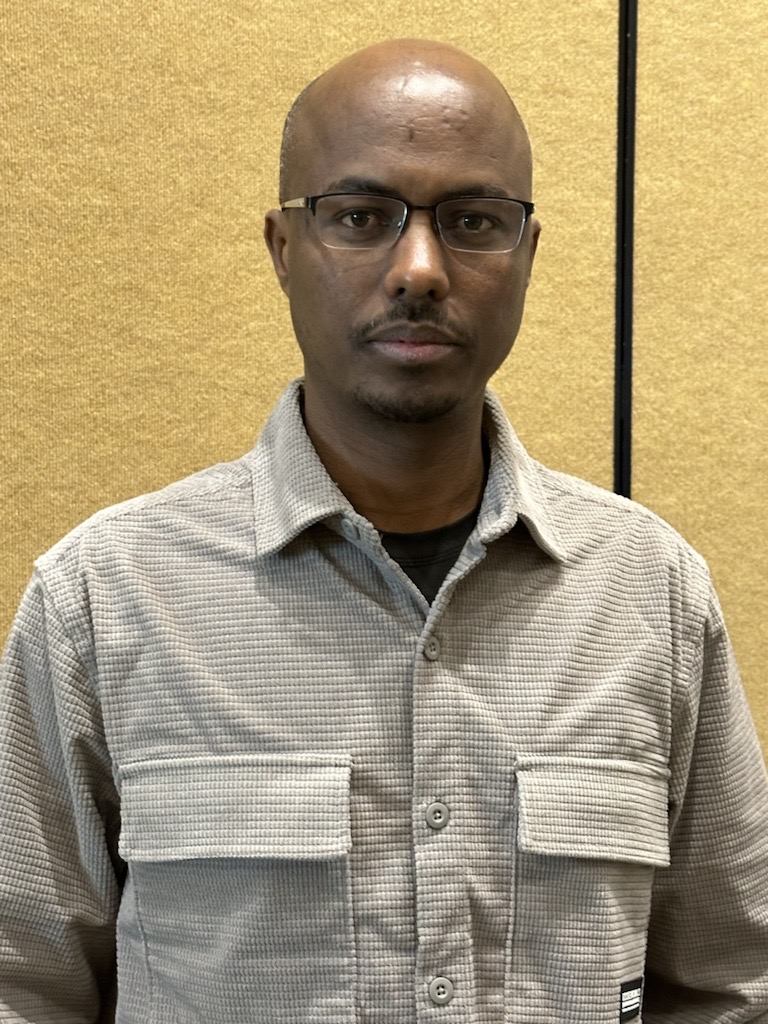

Dr. Gebremedhin Gebremeskel Haile walks into the room around ten minutes earlier than our agreed-upon meeting time. I extend out a hand to shake his, but I quickly realize that Cheeto dust covers my fingers from the bag I was indulging in seconds earlier. I excuse myself to wash my hands and as the faucet runs, I think about everything I’ve gathered about Dr. Haile as research for this interview. Prior to meeting him, I had read his faculty page, which in great detail outlined his academic interests and accomplishments. I already had a decently clear idea of what I’d write about – or so I thought. In my conversation with Dr. Haile, I learned much more about him and the world than I initially expected to.

Dr. Haile started off by telling me about his childhood. Originally from the countryside of the Tigray Region, Ethiopia, Dr. Haile had a peaceful childhood like any other kid. He tended to his family’s cattle and goats in his home, a village named Maygundi. For grades sixth to twelve, Dr. Haile completed his schooling in a nearby town named Enticho. After obtaining his certificate to move onto university, Dr. Haile got his BSc Soil and Water Engineering and

Management at Haramaya University, which is located in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia. After obtaining his Bachelor’s, Dr. Haile moved back home to work at the Tigray Agricultural

Research Institute as a research officer in irrigation and water sources. Later, he obtained his Masters in Irrigation Engineering at Haramaya. After this, he returned to Tigray again to help his community, particularly the farmers in his community, with the knowledge he’d gathered from his studies. When I asked him about why he took part in community service, he said that growing up, there was a shortage of clean water in his village and surrounding areas, so he had a personal interest in teaching others how to deal with this issue.

While he was working and helping people in his hometown, Dr Haile said that, “In the meantime, I was applying for scholarships, trying to upgrade myself by studying more. During my Master’s study, I used this time to publish papers.” The way in which Dr. Haile spoke about research, paper-writing and reading struck me: it was rare to find the kind of passion and tenacity that Dr. Haile exhibited when he recounted his life experiences and academic interests. This sort of fire is what eventually earned Dr. Haile the CAS-TWAS President’s Fellowship, a scholarship that allowed him to earn his PhD at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. For his doctoral research, he studied drought in about eleven countries in the East African region. He published five great papers in the three years it took for him to complete his PhD. Before graduation, he applied for postdoctoral research opportunities and got some positions in China and Macau.

Before beginning this work, he went home and unfortunately could not return to China due to the COVID-19 outbreak. So, Dr. Haile stayed home in Tigray and defended his PhD via Zoom. In Tigray, he worked as a senior researcher at his research institute until war broke out and the Tigray Region was under siege by the Ethiopian government. Dr. Haile kept his composure and even weaved a wry joke or two into his retelling of the difficult experiences in the war. Getting caught in the crossfire of an ethnic cleansing campaign is what led to Dr. Haile’s Scholar at Risk status, which he applied to via the United Nations satellite internet whenever he got access to that. Even when the situation came down to life or death, Dr. Haile’s dedication to his work and research never died down. In fact, he says his research was a stress reliever for him. I looked at Dr. Haile a little funny when he said this.

I think I understood Dr. Haile’s dedication to his passions as a form of rebellion; there is immense strength in trying to continue your everyday activities when there is danger every which way you look. After exactly two years, the war began to calm down because a peace accord was signed. Whenever he got access to the internet, he checked his email and wrote to his supervisor in China. Soon, though

not without challenges, he got an emergency visa in the capital city, Addis Ababa, and got back to China. While he was in Addis Ababa, he interviewed with the Scholar at Risk Program and with Wesleyan while he was in China and finally got here in July of 2023. The Tigray Region is still reeling from the effects of the war and due to it still not being totally safe in the region, Dr. Haile worries for and misses his family.

This spring, Dr. Haile is set to teach a course in the Earth & Environmental Sciences department called Introduction to GIS (Geographical Information Systems). When I asked Dr. Haile about what drives him to be a teacher and mentor as part of his career, he answered that teaching allows him to do on-the-ground work and be actively engaged in his communities – essentially making him highly-skilled with both theory and practice. “Grassroots experience is extremely important,” says Dr. Haile.

At the end of the conversation, Dr. Haile and I talked about climate change and all the things he looks forward to at Wesleyan and beyond. Dr Haile underscores the fact that climate change is a global issue affecting everyone. “There is plenty of rainfall in some areas, and drought in some areas – this disparity in rainfall is due to climate change.” He urges people to consider the effects of climate change and to be grateful for the peace of mind that one gets from having consistent access to safe water because “Peace of mind in general is always important to have a good life.” Since coming to the US, there are many people who have supported him with logistics and getting access to the facilities needed to produce his research and have a peaceful life, which he is very grateful for. As a final thought, Dr. Haile wants readers to know that he wholeheartedly loves his work and it’s this love that got him here. So, love what you do – you might change the world with it.