Megan Levan, Environmental Studies and South Asia Studies in a Global Context, Class of ’22

This summer, I got the opportunity to attend the Insects to Feed the World Conference in Quebec City, Canada, to continue my journey with entomophagy. Entomophagy is the practice of eating insects. There are currently over 2,000 species of insects that are known to be consumed by humans worldwide and over a quarter of the globe already incorporates these insects into their diets. Many insect species can be farmed using fewer resources and less physical space than other animal proteins. They are also delicious! As current food systems continue to degrade land and fail the burgeoning population, insects have been lauded as a sustainable superfood of the future, both for people living in generally bug-averse cultures and practiced entomophages alike!

Arnold Van Huis, the author of the UN FAO’s 2013 report that is credited for inspiring the modern entomophagy movement in generally bug-averse cultures, gave the first keynote address. I was absolutely starstruck.

After wrapping up my thesis about the entomophagy industry in the United States last semester, I was antsy to learn more about the edible insect industry on a global scale. The Insects to Feed the World conference was a great way to do just that. Insects to Feed the World brought together 571 delegates from 58 countries to discuss insects both as feed for pets and livestock as well as insects for human consumption. Over the course of the week, I learned so much! Here are some of my biggest and buggiest takeaways:

Mealworm lasagna for lunch! There was always a vegetarian and an entotarian option for meals, and black ants and mealworms were almost always on the menu.

- I was surprised to see that the majority of the companies represented at the conference work with black soldier flies as animal feed. Black soldier fly larvae have gained popularity due to their ability to chow through any kind of food waste, where other insects need more specific diets that are harder to source from waste streams. Many companies working with BSF are working on diverting food waste from the landfill to feed their larvae and create a nutrient-rich animal protein for pets and other animals. Unfortunately, many of these businesses are not currently looking into BSF larvae for human consumption because of the current regulatory framework guiding edible insect rearing/consumption, which is a shame. I tried some dried BSF larvae and they tasted like a crispier, somewhat parmesan-flavored mealworm.

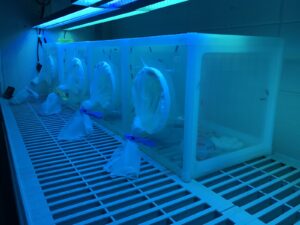

Black soldier flies in the lab at the University of Laval where they are reared on a small scale for student research. The pupae hidden in one container at the bottom of the net cage emerge as flies which then mate and lay their eggs in a different container at the bottom of the net to be raised into new larvae.

- There is so much going on in Canada, and especially in Quebec! After spending the last year and a half focusing on the insect-based products available in the United States, it was incredible to see just how much is happening with our neighbors. One cricket-based company, Aspire, is currently in the process of opening the largest human-grade cricket farm in the world in London, Ontario. The entire farm will be automated, which will hopefully mean lower prices for cricket-based foods in the near future. Meanwhile, smaller-scale mealworm and cricket farms are popping up all around Canada. I got to tour TriCycle, a medium-scale, human-grade mealworm farm in Montreal, that feeds their mealworms food waste from a local bakery and juicery.

Crunchy, dried black soldier fly larvae that are raised and sold for chickens and other pets (but that didn’t stop me from snacking).

I also was able to taste a cricket-flour bread from the company CrickBread. While I typically love eating insects in their full-bodied, shining glory, seeing insect-based products that move beyond the snack products we often find in the U.S. was very exciting! Companies like CrickBread offer a product that consumers can easily incorporate into their everyday diet, eliminating some of the novelty/gimmick factor that has been a challenge for many insect-based businesses trying to get consumers to hop on the entomophagy bandwagon.

The TriCycle mealworm farm. Mealworms can be farmed in open stacked crates at all stages of life since the beetles don’t fly, which is helpful for optimizing space.

- My final buggy takeaway is likely the least surprising: there are so many interesting people involved in the entomophagy and insects-as-feed industry. One of the main highlights of the conference was meeting people from all over the world who share my passion for (edible) insects. It was especially fun to meet fellow students specializing in so many different industry-related fields. One new friend was working specifically on insect frass (poop) and the ways in which it can enhance nutrients in soil. Another was focused on consumer acceptance of edible insects in Australia.Yet another was creating a mealworm-based falafel to be served in the dining halls at the University of Vermont, using mealworms he grows using pre-consumer food waste from the dining halls themselves. I, personally, plan on continuing my work in entomophagy advocacy and education in Spain next year, and hopefully raising some mealworms on the side! What is certain is that after meeting so many buggy friends, I am beyond excited to see what’s in store for entomophagy in the near future. I can’t wait for IFW 2026! I ant-icipate great things.Email mlevan@wesleyan.edu if you have any questions about entomophagy in the United States, or if you have a burning desire to read her thesis!

Eating a scorpion with Nathan, another recent graduate from Cornell. Fun fact: all scorpions glow under UV light.

Cathy Mbuyi brought a bag of caterpillars for conference-goers to taste! Her caterpillars were very crunchy and their flavor was a bit nutty. They are typically eaten rehydrated in stews or relishes or baked into breads.

One of the booths at Eating Insects North, an event concluding the conference at which insect-based businesses could share their products with the public. The cotton candy crickets are EntoLife’s most popular flavor!